New Poll Finds Evangelicals’ Favorite Heresies

Oct 30, 2014 19:04:42 GMT -5

Post by Shoshanna on Oct 30, 2014 19:04:42 GMT -5

Seems a lot of people mistakenly believe they're saved. They're in for a rude awakening!

New Poll Finds Evangelicals’ Favorite Heresies

Survey finds many American evangelicals hold unorthodox views on the Trinity, salvation, and other doctrines.

Kevin P. Emmert / posted October 28, 2014

New Poll Finds Evangelicals’ Favorite Heresies

Icon of the Fathers at the First Council of Nicaea

Most American evangelicals hold views condemned as heretical by some of the most important councils of the early church.

A survey released today by LifeWay Research for Ligonier Ministries “reveals a significant level of theological confusion,” said Stephen Nichols, Ligonier’s chief academic officer. Many evangelicals do not have orthodox views about either God or humans, especially on questions of salvation and the Holy Spirit, he said.

Evangelicals did score high on several points. Nearly all believe that Jesus Christ rose from the dead (96%), and that salvation is found through Jesus alone (92%). Strong majorities said that God is sovereign over all people (89%) and that the Bible is the Word of God (88%).

And in some cases the problem seems to be uncertainty rather than heresy. For example, only 6 percent of evangelicals think the Book of Mormon is a revelation from God, but an additional 18 percent aren’t sure and think it might be.

Jesus, Almost as Good as His Father?

Almost all evangelicals say they believe in the Trinity (96%) and that Jesus is fully human and fully divine (88%).

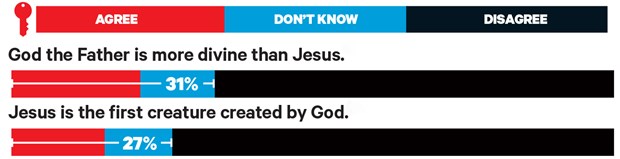

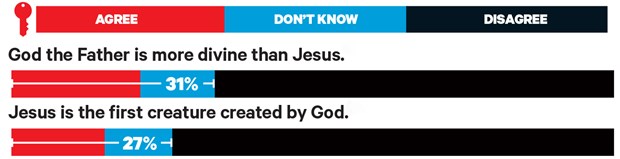

But nearly a quarter (22%) said God the Father is more divine than Jesus, and 9 percent weren’t sure. Further, 16 percent say Jesus was the first creature created by God, while 11 percent were unsure.

No doubt, phrases like “only begotten Son” (John 3:16) and “firstborn of all creation” (Col. 1:15) have led others in history to hold these views, too. In the fourth century, a priest from Libya named Arius (c.250–336) announced, “If the Father begat the Son, then he who was begotten had a beginning. … There was a time when the Son was not.” The idea, known as Arianism, gained wide appeal, even among clergy. But it did not go unopposed. Theologians Alexander and Athanasius of Alexandria, Egypt, argued that Arius denied Christ’s true divinity. Christ is not of similar substance to God, they explained, but of the same substance.

Believing the debate could split the Roman Empire, Emperor Constantine convened the first ecumenical church council in Nicaea in A.D. 325. The council, comprising over 300 bishops, rejected Arianism as heresy and maintained that Jesus shares the same eternal substance with the Father. Orthodoxy struggled to gain popular approval, however, and several heresies revolving around Jesus continued to spread. At the second ecumenical council in Constantinople in 381, church leaders reiterated their condemnation of Arianism and enlarged the Nicene Creed to describe Jesus as “the only-begotten Son of God, begotten of the Father before all worlds, Light of Light, very God of very God, begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father, by whom all things were made.”

In other words, the Son is not a created being, nor can he be less divine than the Father.

The Holy Spirit: May the Force Be with You?

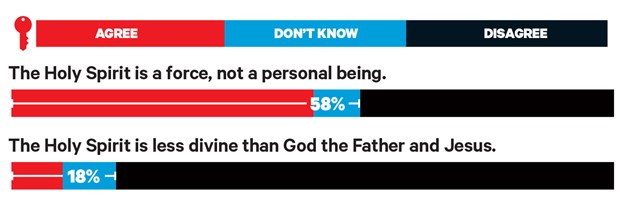

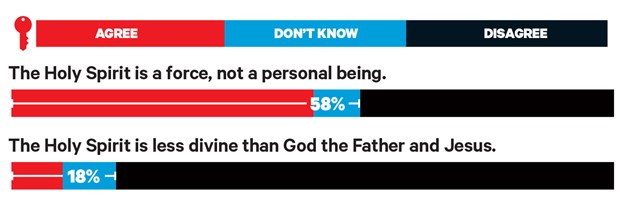

But if evangelicals sometime misunderstand doctrines about Jesus, the third member of the Trinity has it much worse. More than half (51%) said the Holy Spirit is a force, not a personal being. Seven percent weren’t sure, while only 42 percent affirmed that the Spirit is a person.

And 9 percent said the Holy Spirit is less divine than God the Father and Jesus. The same percentage answered “not sure.”

Like Arianism, confusion over the nature and identity of the Spirit dates to the early church. During the latter half of the fourth century, sects like Semi-Arians and Pneumatomachi (Greek for “Spirit fighters”) believed “in the Holy Spirit”—as the First Council of Nicaea (A.D. 325) taught—but said the Spirit was of a different essence from the Father and the Son. Some said the Spirit was a creature, and others understood the Spirit to be a force or power, not a person of the Trinity.

At Constantinople, 150 bishops assembled to discuss these heresies, among other issues, and affirmed that “the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit have a single Godhead and power and substance, a dignity deserving the same honor and a co-eternal sovereignty, in three most perfect hypostases, or three perfect persons.” Affirming the full divinity and personhood of the Holy Spirit, the church ruled out Semi-Arianism and Pneumatomachianism.

Salvation: Who Makes the First Move?

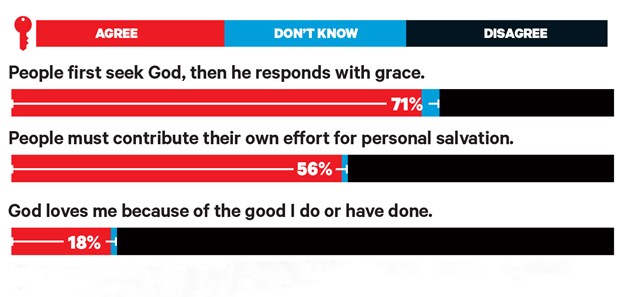

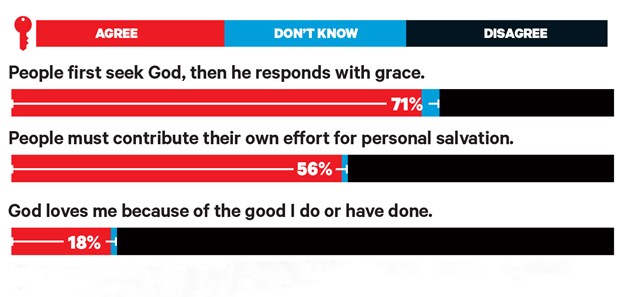

Human nature and salvation were other areas of confusion for respondents. Two out of three (68%) said that a person obtains peace with God by seeking God first, and then God responds with grace. A similar percentage (67%) said people have the ability to turn to God on the own initiative. Yet half (54%) also think salvation begins with God acting first. So which is it?

In the fifth century, a British monk named Pelagius reportedly argued that people can choose God by the strength of their own will. Adam’s sin, he taught, did not sabotage human freedom, so we still have the ability to choose and follow God by the strength of our will.

His school of thought, known as Pelagianism, was denounced at the Council of Carthage in 418 and later at the Council of Ephesus in 431. A variation, known as Semipelagianism, cropped up shortly thereafter, affirming original sin but teaching that humans take the initiative in salvation. The Council of Orange in 529 rejected Semipelagianism as heretical, maintaining that faith is a gift of God’s grace and does not originate in ourselves.

More than half of survey participants (55%) said people have to contribute to their own salvation. This, however, is a debated issue. Some Christians—such as Roman Catholics, Orthodox, and certain Protestants—believe humans cooperate with God’s grace in salvation. Others believe our efforts can contribute nothing, though a response to God’s grace is a necessary element of conversion. Nevertheless, historic Christian teaching in all branches maintains that whatever role humans play is ultimately inspired by the work of God’s Spirit. The Council of Orange put it this way:

If anyone says that God has mercy upon us when, apart from his grace, we believe, will, desire, strive, labor, pray, watch, study, seek, ask, or knock, but does not confess that it is by the infusion and inspiration of the Holy Spirit within us that we have the faith, the will, or the strength to do all these things as we ought; or if anyone makes the assistance of grace depend on the humility or obedience of man and does not agree that it is a gift of grace itself that we are obedient and humble, he contradicts the Apostle who says, “What have you that you did not receive?” (1 Cor. 4:7), and, “But by the grace of God I am what I am” (1 Cor. 15:10).

A Historic Problem with Historical Solutions

Ligonier’s Nichols said that while the survey results are disappointing, they’re not unique to our time or culture, or irreversible. “The church in every age has faced theological confusion and heresy. In this survey we see a wake-up call to the church. We cannot assume the next generation—or even this present one—will catch an orthodox theology merely by being in the church,” he said.

John Stackhouse, professor of theology and culture at Regent College in Vancouver, agrees. “We continue to hold adult Christian education in low regard,” he said. “A sermon on Sunday morning and a conversational Bible study during the week won’t get the job done of informing and transforming people’s minds along the lines of orthodox Christian belief.”

The Lifeway survey also found that 9 in 10 evangelicals believe the local church does not have authority to say a person is not a Christian. Read expert repsonses: Does My Local Church Have Authority to Declare That I Am Not a Christian?

But Stackhouse said he’s not sure that stronger efforts by churches to instruct their congregants would raise the numbers. The survey, he noted, was of self-described evangelicals, and many of those with unorthodox beliefs may not be regular church attenders. “We continue to have a severe public relations problem regarding the term evangelical,” he said.

(Lifeway Research says the survey used was a balanced online panel in February and March. Of the survey’s initial 3,000 responses, this report looked at the 557 who came from Protestants who described themselves as evangelical—which would be about 19 percent of the American population.)

Timothy Larsen, professor of Christian thought at Wheaton College, is similarly cautious. He said the same survey questions should be asked over time in order to determine what sort of trend exists. “What matters is not what self-identified evangelicals know or believe, but whether they are being discipled over time into mature believers,” he said. “If the answers are not getting better with more Christian discipleship, that would be alarming.”

Larsen was encouraged, however, by several statistics. He said he would have guessed fewer than 96 percent would have affirmed belief in the Trinity. Howard Snyder—a former professor at United Theological Seminary, Asbury Seminary, and Tyndale Seminary—expressed similar optimism at the survey’s high number on that point, though he said the survey reveals the need for clearer teaching on what belief in the Trinity means. “Western Christianity, not just evangelicals, have viewed the Trinity as ‘a mathematical problem to be solved,’ not as a central revelation of the personal and tri-personal nature of God,” said Snyder. For him, the doctrine of the Trinity is not an abstract concept but a fundamental Christian truth that informs us about the God we worship, who we are as humans, and all creation.

Snyder isn't alone. Beth Felker Jones, professor of theology at Wheaton College, said, "Orthodoxy is life-giving, and God's people need access to it." Participants who gave unorthdox answers are not heretics, but probably lacked quality resources, she said. "Church leaders need to be able to teach the truth of the faith clearly and accurately, and we need to be able to show people why this matters for our lives."

For Nichols, one way forward in understanding God and ourselves is to consult the historic church. “While slightly over half see value in church history, [nearly] 70 percent have no place for creeds in their personal discipleship,” he said. For Nichols, the church’s knowledge of its past will determine its future. Knowing heresies and how they were overcome, he says, will help the church stay on the right track theologically.

The poll has a margin of error of +1.8 percent with a confidence interval of 95 percent.

link

New Poll Finds Evangelicals’ Favorite Heresies

Survey finds many American evangelicals hold unorthodox views on the Trinity, salvation, and other doctrines.

Kevin P. Emmert / posted October 28, 2014

New Poll Finds Evangelicals’ Favorite Heresies

Icon of the Fathers at the First Council of Nicaea

Most American evangelicals hold views condemned as heretical by some of the most important councils of the early church.

A survey released today by LifeWay Research for Ligonier Ministries “reveals a significant level of theological confusion,” said Stephen Nichols, Ligonier’s chief academic officer. Many evangelicals do not have orthodox views about either God or humans, especially on questions of salvation and the Holy Spirit, he said.

Evangelicals did score high on several points. Nearly all believe that Jesus Christ rose from the dead (96%), and that salvation is found through Jesus alone (92%). Strong majorities said that God is sovereign over all people (89%) and that the Bible is the Word of God (88%).

And in some cases the problem seems to be uncertainty rather than heresy. For example, only 6 percent of evangelicals think the Book of Mormon is a revelation from God, but an additional 18 percent aren’t sure and think it might be.

Jesus, Almost as Good as His Father?

Almost all evangelicals say they believe in the Trinity (96%) and that Jesus is fully human and fully divine (88%).

But nearly a quarter (22%) said God the Father is more divine than Jesus, and 9 percent weren’t sure. Further, 16 percent say Jesus was the first creature created by God, while 11 percent were unsure.

No doubt, phrases like “only begotten Son” (John 3:16) and “firstborn of all creation” (Col. 1:15) have led others in history to hold these views, too. In the fourth century, a priest from Libya named Arius (c.250–336) announced, “If the Father begat the Son, then he who was begotten had a beginning. … There was a time when the Son was not.” The idea, known as Arianism, gained wide appeal, even among clergy. But it did not go unopposed. Theologians Alexander and Athanasius of Alexandria, Egypt, argued that Arius denied Christ’s true divinity. Christ is not of similar substance to God, they explained, but of the same substance.

Believing the debate could split the Roman Empire, Emperor Constantine convened the first ecumenical church council in Nicaea in A.D. 325. The council, comprising over 300 bishops, rejected Arianism as heresy and maintained that Jesus shares the same eternal substance with the Father. Orthodoxy struggled to gain popular approval, however, and several heresies revolving around Jesus continued to spread. At the second ecumenical council in Constantinople in 381, church leaders reiterated their condemnation of Arianism and enlarged the Nicene Creed to describe Jesus as “the only-begotten Son of God, begotten of the Father before all worlds, Light of Light, very God of very God, begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father, by whom all things were made.”

In other words, the Son is not a created being, nor can he be less divine than the Father.

The Holy Spirit: May the Force Be with You?

But if evangelicals sometime misunderstand doctrines about Jesus, the third member of the Trinity has it much worse. More than half (51%) said the Holy Spirit is a force, not a personal being. Seven percent weren’t sure, while only 42 percent affirmed that the Spirit is a person.

And 9 percent said the Holy Spirit is less divine than God the Father and Jesus. The same percentage answered “not sure.”

Like Arianism, confusion over the nature and identity of the Spirit dates to the early church. During the latter half of the fourth century, sects like Semi-Arians and Pneumatomachi (Greek for “Spirit fighters”) believed “in the Holy Spirit”—as the First Council of Nicaea (A.D. 325) taught—but said the Spirit was of a different essence from the Father and the Son. Some said the Spirit was a creature, and others understood the Spirit to be a force or power, not a person of the Trinity.

At Constantinople, 150 bishops assembled to discuss these heresies, among other issues, and affirmed that “the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit have a single Godhead and power and substance, a dignity deserving the same honor and a co-eternal sovereignty, in three most perfect hypostases, or three perfect persons.” Affirming the full divinity and personhood of the Holy Spirit, the church ruled out Semi-Arianism and Pneumatomachianism.

Salvation: Who Makes the First Move?

Human nature and salvation were other areas of confusion for respondents. Two out of three (68%) said that a person obtains peace with God by seeking God first, and then God responds with grace. A similar percentage (67%) said people have the ability to turn to God on the own initiative. Yet half (54%) also think salvation begins with God acting first. So which is it?

In the fifth century, a British monk named Pelagius reportedly argued that people can choose God by the strength of their own will. Adam’s sin, he taught, did not sabotage human freedom, so we still have the ability to choose and follow God by the strength of our will.

His school of thought, known as Pelagianism, was denounced at the Council of Carthage in 418 and later at the Council of Ephesus in 431. A variation, known as Semipelagianism, cropped up shortly thereafter, affirming original sin but teaching that humans take the initiative in salvation. The Council of Orange in 529 rejected Semipelagianism as heretical, maintaining that faith is a gift of God’s grace and does not originate in ourselves.

More than half of survey participants (55%) said people have to contribute to their own salvation. This, however, is a debated issue. Some Christians—such as Roman Catholics, Orthodox, and certain Protestants—believe humans cooperate with God’s grace in salvation. Others believe our efforts can contribute nothing, though a response to God’s grace is a necessary element of conversion. Nevertheless, historic Christian teaching in all branches maintains that whatever role humans play is ultimately inspired by the work of God’s Spirit. The Council of Orange put it this way:

If anyone says that God has mercy upon us when, apart from his grace, we believe, will, desire, strive, labor, pray, watch, study, seek, ask, or knock, but does not confess that it is by the infusion and inspiration of the Holy Spirit within us that we have the faith, the will, or the strength to do all these things as we ought; or if anyone makes the assistance of grace depend on the humility or obedience of man and does not agree that it is a gift of grace itself that we are obedient and humble, he contradicts the Apostle who says, “What have you that you did not receive?” (1 Cor. 4:7), and, “But by the grace of God I am what I am” (1 Cor. 15:10).

A Historic Problem with Historical Solutions

Ligonier’s Nichols said that while the survey results are disappointing, they’re not unique to our time or culture, or irreversible. “The church in every age has faced theological confusion and heresy. In this survey we see a wake-up call to the church. We cannot assume the next generation—or even this present one—will catch an orthodox theology merely by being in the church,” he said.

John Stackhouse, professor of theology and culture at Regent College in Vancouver, agrees. “We continue to hold adult Christian education in low regard,” he said. “A sermon on Sunday morning and a conversational Bible study during the week won’t get the job done of informing and transforming people’s minds along the lines of orthodox Christian belief.”

The Lifeway survey also found that 9 in 10 evangelicals believe the local church does not have authority to say a person is not a Christian. Read expert repsonses: Does My Local Church Have Authority to Declare That I Am Not a Christian?

But Stackhouse said he’s not sure that stronger efforts by churches to instruct their congregants would raise the numbers. The survey, he noted, was of self-described evangelicals, and many of those with unorthodox beliefs may not be regular church attenders. “We continue to have a severe public relations problem regarding the term evangelical,” he said.

(Lifeway Research says the survey used was a balanced online panel in February and March. Of the survey’s initial 3,000 responses, this report looked at the 557 who came from Protestants who described themselves as evangelical—which would be about 19 percent of the American population.)

Timothy Larsen, professor of Christian thought at Wheaton College, is similarly cautious. He said the same survey questions should be asked over time in order to determine what sort of trend exists. “What matters is not what self-identified evangelicals know or believe, but whether they are being discipled over time into mature believers,” he said. “If the answers are not getting better with more Christian discipleship, that would be alarming.”

Larsen was encouraged, however, by several statistics. He said he would have guessed fewer than 96 percent would have affirmed belief in the Trinity. Howard Snyder—a former professor at United Theological Seminary, Asbury Seminary, and Tyndale Seminary—expressed similar optimism at the survey’s high number on that point, though he said the survey reveals the need for clearer teaching on what belief in the Trinity means. “Western Christianity, not just evangelicals, have viewed the Trinity as ‘a mathematical problem to be solved,’ not as a central revelation of the personal and tri-personal nature of God,” said Snyder. For him, the doctrine of the Trinity is not an abstract concept but a fundamental Christian truth that informs us about the God we worship, who we are as humans, and all creation.

Snyder isn't alone. Beth Felker Jones, professor of theology at Wheaton College, said, "Orthodoxy is life-giving, and God's people need access to it." Participants who gave unorthdox answers are not heretics, but probably lacked quality resources, she said. "Church leaders need to be able to teach the truth of the faith clearly and accurately, and we need to be able to show people why this matters for our lives."

For Nichols, one way forward in understanding God and ourselves is to consult the historic church. “While slightly over half see value in church history, [nearly] 70 percent have no place for creeds in their personal discipleship,” he said. For Nichols, the church’s knowledge of its past will determine its future. Knowing heresies and how they were overcome, he says, will help the church stay on the right track theologically.

The poll has a margin of error of +1.8 percent with a confidence interval of 95 percent.

link